Is nickel headed for a sustained decline?

Nickel is a naturally occurring, lustrous, silvery-white metal. It is the fifth most common element on earth and occurs extensively in the earth's crust. However, most of the nickel is inaccessible in the core of the earth. Some of the key characteristics of nickel are its high melting point, resistance against corrosion and oxidation, ductility and catalytical properties, ease of deposit by electroplating and formation of alloys readily. Nickel is widely used in over 3 lakh products. The biggest use is in alloying, particularly with chromium and other metals to produce stainless and heat-resisting steels. In homes, these are found in pots and pans, kitchen sinks, and so on; they also find their way in buildings, food processing equipment, medical equipment, and chemical plants.

There are two different forms of nickel:

-

On the London Metal Exchange, nickel is traded as Class 1 nickel, which must be at least 99.8% pure. However, roughly half of the world's nickel is Class 2 metal, with the majority of it is in the form of ferronickel and nickel pig iron, which can be easily processed into stainless steel in Chinese smelters.

-

These two products, in turn, are usually made from quite different ores. Nickel sulphide deposits are perfect for processing high-purity products such as Class 1 nickel, but they're rare and only found in a few temperate regions.

-

Class 2 nickel which is largely generated from nickel laterite, a lower-grade ore that is easily strip-mined from worn earth in Southeast Asia and other regions of the tropics, has seen a booming market in recent years.

-

Russia produces only around 9% of the world's nickel, but it has a third of the world's nickel sulphide ore. As a result, the classification of its exports has a disproportionately large impact on the price of Class 1 metal traded on the LME.

-

This grade is also the best for making nickel sulphate, a chemical that will become increasingly important in the coming years due to its application in electric vehicle batteries.

Nickel is mainly used in the production of stainless steel and other alloys and can be found in food preparation equipment, mobile phones, medical equipment, transport, buildings, power generation. The biggest producers of nickel are Indonesia, the Philippines, Russia, New Caledonia, Australia, Canada, Brazil, China and Cuba. The standard contract has a weight of 6 tonnes. The nickel prices displayed in Trading Economics are based on over-the-counter (OTC) and contract for difference (CFD) financial instruments

Nickel futures hit $100,000 for the first time on Tuesday, March 8, 2022, nearly tripling in value as western sanctions on Russia over its invasion of Ukraine raised concerns about metal supplies. The London Metal Exchange has halted trading in the nickel market due to an unprecedented move and has stated that it is unlikely to reopen until Friday. The LME also stated that, even once trading resumes, it will only operate during European hours at first, with a daily price cap of 10%. Russia produces roughly 10% of the world's nickel, which is mostly used in stainless steel and electric vehicle batteries.

Prior to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, nickel was already on the rise as strong demand from the stainless steel and battery industries depleted inventories, which now stand at 76,830 tonnes in LME-registered warehouses, the lowest level since 2019.

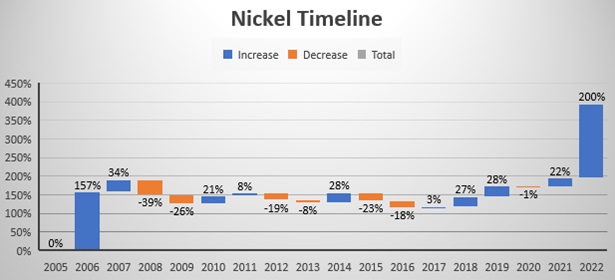

Sudden Rise in 2006

The storm of M&A raved over the industries of steel and metals resources in 2006 and the nickel industry was unable to be unrelated to this movement. Inco was attacked to be taken over by other companies but CVRD (Rio Doce) of Brazil has finally acquired Inco for US$20,000 million.

The reasons, why share prices of nickel producers have risen to an extraordinary extent, were due to competitions between major resources companies and also soared prices of such base metals like copper and zinc listed on LME.

It was initially anticipated that the soared nickel price should cause to reduce the demand for stainless steel and, as a phenomenon of boomerang, nickel price would start to fall from autumn of 2006, but this expectation was entirely disappointed.

In the course of the battles to acquire nickel producers, quantities of nickel to be produced by the existing refineries in 2006 were becoming lower than originally scheduled.

At Yabulu refinery of QNI / Australia: The decreased nickel production in April - June quarter of 2006 and October - December quarter was due to the difficulties to have a normal operation for the work to expand facilities.

At nickel producers (Empress and Bindura) / Zimbabwe: Because of a short supply of electric power and a lower content of nickel in crude ore at their nickel mines, quantities of nickel are inclining to decrease gradually.

Sudden rise in 2022

Nickel prices have risen by 90% to a new high due to fears of supply bottlenecks from a major supplier. Russia

Russia is the world's third-largest nickel producer, with stainless steel accounting for about two-thirds of total nickel production. Nickel is also important in the developing market for electric vehicle batteries.

Although no sanctions against the Russian commodity complex have been issued, the US and its allies are allegedly discussing limiting oil supplies. Concerns about possible limitations on other Russian exports arose as a result of this.

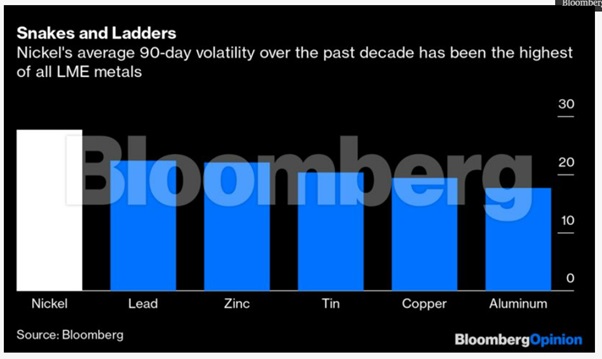

Nickel is the most volatile metal

Many metals are manufactured using standardised processes. Since the 19th century, the Hall-Heroult smelting method has produced nearly all of the world's aluminium. Because there is only one technology to consider, pricing is reasonably predictable.

Nickel is unique in that it has a diverse range of processes and end-use industries that combine in unanticipated ways. Price swings are crucial to nick's survival.

However, the ability to turn lower-grade Class 2 nickel into higher-grade Class 1 metal should bring pricing back in line over time. When LME prices are north of $25,000 per metric tonne, upgrading Class 2 metal to a higher-quality product is a solid investment.

We saw something similar during nickel's most recent dramatic price increase, when the metal nearly quadrupled in price in the two years leading up to April 2007, then losing three-quarters of its value in the two years following, as Russia produces only around 9% of the world's nickel, but it has a third of the world's nickel sulphide ore.

As a result, the classification of its exports has a disproportionately large impact on the price of Class 1 metal traded on the LME.

This grade is also the best for making nickel sulphate, a chemical that will become increasingly important in the coming years due to its application in electric vehicle batteries. Lower-grade ferronickel and nickel pig iron technologies have snatched market share from higher-grade ferronickel and nickel pig iron technologies.

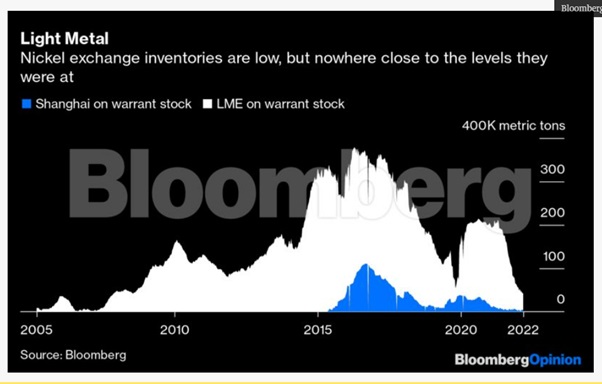

Inventories are low, but not desperately so.

The majority of global metal trade takes place in direct contract connections between a limited number of producers and customers, rather than on exchanges like the LME.

The metal that makes its way to the exchanges is usually surplus goods that the same manufacturers and consumers buy and sell to hedge the prices they're getting in the physical market and establish a benchmark price against which they may benchmark their trades. Traders keep a close eye on metal stockpiles housed in exchange warehouses because they're considered an indication of how tight the overall market is. Those stocks, particularly those of the on-warrant metal that is available to traders, have been plummeting to historic lows. Still, with 36,654 tonnes of deliverable metal in the LME's warehouses, we've come a long way from 2006, when the worldwide stockpile of 870 tonnes could fit on one half of a tennis court.

Low supply is not the only reason behind the price rise: - Short Squeeze

Xiang Guangda- who controls the world's largest nickel producer, Tsingshan Holding Group Co., is facing billions of dollars in mark-to-market losses after this week's price spike. Nickel rocketed to a record high above $100,000 a ton on Tuesday before trading was suspended. Xiang has closed out part of his company's short position and is considering whether to exit the water altogether. Takingshan has been struggling to pay margin calls to its brokers, according to people familiar with the situation. Traders must deposit cash, known as "margin," with their brokers regularly to cover potential losses on their positions.

On Monday, one of Tsingshan's brokers failed to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in margin calls on its nickel positions. The LME suspended trades that took place in Asian hours before the suspension - when prices rose from around $50,000 to above $100,000 a ton.

Post a Comment

|

DISCLAIMER |

This report is only for the information of our customers. Recommendations, opinions, or suggestions are given with the understanding that readers acting on this information assume all risks involved. The information provided herein is not to be construed as an offer to buy or sell securities of any kind. ATS and/or its group companies do not as assume any responsibility or liability resulting from the use of such information.